In 1987, New York State enacted legislation to create an Economic Development Zones Program, modelled after the enterprise zones concept, championed by Congressman Jack Kemp. Proponents argued that by reducing taxes in specific geographic areas with high concentrations of poverty and unemployment, existing firms would be more likely to create jobs, and other firms would be encouraged to locate in the areas and create jobs.

Enterprise Zones programs were attractive to policy makers, in part because they were “off budget.” The programs provided financial benefits to companies that, unlike incentive grants, did not require the appropriation of state budget dollars to pay for them.

There is scant evidence that Enterprise Zones programs have been effective. See, for example, this GAO report,[1] which concluded that evaluations of Federal Empowerment Zones and Enterprise Communities could not demonstrate effectiveness, and this study,[2] which was did not show any impact as a result of Enterprise Zones programs in Florida and California. Evaluations of the New York State program found significant administrative problems, but did not find significant benefits.[3] The major problem with the Enterprise Zones concept was that because the tax advantages provided by the program were insufficient to offset the perceived disadvantages of inner city locations, the program did not result in job creation within the zones.

The program generated a cottage industry of consultants who advised businesses on how to take advantage of the benefits, by reorganizing in to new organizations so that existing jobs could be counted as new ones and by modifying zone boundaries, creating gerrymanders, to incorporate specific businesses.

But, over the years, the program was expanded and the benefits deepened. It was renamed the Empire Zones program. More areas were made eligible, yet the areas that the program was initially intended to benefit – distressed inner city communities in New York State – did not see improved conditions. In fact, 20 years after the program’s enactment, they were in significantly worse economic condition. In 1969, upstate cities had poverty rates that were slightly higher than the average for the state. By 2013, most upstate cities had poverty rates that were more than double the state’s.

(Data for cities with populations of less than 100,000 is not available before 1999)

In the end, Economic Development Zones/Empire Zones became an embarrassment to successive governors and Empire State Development because of the difficulties in policing the abuses of the overly complex program, and its lack of success in inducing job creation. Successive legislative efforts to “clean the program up” were met with continued creative approaches to exploit it by businesses. The program was ended in 2010.

Despite the failure of the tax benefits contained in the Economic Development Zones and Empire Zones programs to induce job creation, and despite the administrative difficulties associated with administering the programs, Governors Paterson and Cuomo continued to rely on tax incentives as key elements of their economic development efforts. Governor Paterson initiated the “Excelsior Jobs” tax credit that focuses on providing benefits to companies in industries that make capital investments and/or create new jobs in manufacturing and other sectors of the economy. Governor Cuomo proposed the Start-Up NY program that offered tax-free benefits to certain businesses in selected locations connected to universities and colleges. Both programs were promoted as major initiatives that would significantly improve New York’s economy. But like the Enterprise/Economic Development/Empire Zones, the programs have failed to create significant numbers of jobs. And, the job creation figures reported for them contain many jobs that would likely have been created without the loss of tax revenues.

Problems with Business Tax Incentives

Business tax incentives are similar to incentives provided to buyers of electric cars or insulation for their homes, in that people or companies become eligible by doing something that government considers desirable – conserving energy or creating jobs. But, they contain no “but for” test – users of the credits are not required to show that without the credits they would not do what is being incentivized. As a result, some credits are always wasted on “free riders” — people or companies that would have acted if the credit was not available.

The use of tax policy to incentivize behavior is widespread, and if large enough, credible arguments can be made for their effectiveness. For example, the available federal tax credit for the purchase of a Nissan Leaf, an electric car, is $7,500. The advertised price of a Leaf begins at about $30,000. Similarly, federal credits for energy conserving improvements in households have been as much as a quarter of the cost. While we do not know how many of the people who purchased Nissan Leafs or weatherized their homes did so because of the availability of financial incentives from government, it is likely that some did.

But, while energy conservation incentives have been designed to be large enough to change people’s purchase decisions, state taxes are too small as components of business revenues to make a significant difference in most cases, particularly given the large differences in wage rates, which are a larger portion of business costs, between the United States and competitive locations.

The Tax Foundation published[4] a comparative analysis of total state and local tax costs for representative businesses in seven industries, including manufacturing, distribution, corporate headquarters, research and development, call centers, and retail. From their data, I calculated total state and local tax costs as a percentage of firm operating costs, and compared New York with national medians, and with nearby states.[5] The data shows that state and local tax costs are a very small percentage of total firm operating costs, and that differences between states are even smaller.

New York State had higher total state and local tax costs than the national median for most types of businesses, but the differences ranged from 0.7% more for call centers, to 1.8% more for research and development facilities. For manufacturers, New York’s total tax costs were lower than the national median, but again the difference between state and local tax costs for manufacturers in New York State and for manufacturers in other states was less than 1% of operating costs.

Compared to neighboring states, the picture was similar. New York state and local tax costs were higher for some businesses, but lower for others. But, in most cases, variations in other factors in the cost of production could be large enough to significantly change the relative advantage of differing locations.

In many cases, state taxes are too small a component of business revenues to make a significant difference in comparative location costs. Fifty years ago, American businesses competed with businesses in other locations in the United States. Differences in wages, construction and transportation costs were relatively small. Today, with globalization, for manufacturers and other businesses that can move operations offshore, the large difference in wage costs between any state in the United States and in low wage locations outside the United States would swamp differences in company operating costs resulting from differences in state and local taxes.

While manufacturing cost structures vary widely,[6] on average, labor is estimated to account for 21% of manufacturing costs.[7] In an article examining China’s manufacturing cost advantage, Peter Navarro, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Irvine, estimates that the cost of labor in China, adjusted for productivity differences, is 18% of that in the United States. As a result, Navarro estimates that manufacturers would save 17% of manufacturing costs by producing in China, compared to the United States.

Business locations are not based solely on cost factors – labor availability, site quality, transportation, quality of life and other factors come into play. But, available evidence shows that differences in state and local tax levels are relatively small factors in business costs, and that adjusting state tax structures to reduce business tax burdens has limited impact.

Repeating Failed Policies: The Excelsior Jobs Program

When the Excelsior Jobs program was created in 2010, Governor David Paterson said “I’m pleased that the Excelsior Jobs Program, a streamlined economic development effort that will support significant potential for private sector economic growth, is now available in the marketplace to encourage businesses to grow and invest in New York.”[8]

Eligible industries are those that could create net new jobs in New York State, not those, like most retail jobs, that simply move jobs from one company in New York State to another in the State. The program description states, “The Program is limited to firms making a substantial commitment to growth – either in employment or through investing significant capital in a New York facility…The Job Growth Track comprises 75% of the Program and includes all firms in targeted industries creating new jobs in New York.” While the program requires a commitment to job growth and/or investment, it does not limit program benefits to firms that would not expand or locate in New York State without the assistance.

The program requires that participants receving credits for job creation or investment have a positive benefit/cost ratio, defined as “total investment, wages and benefits divided by the value of the tax credits, or 10 to 1 or greater. The program provides a refundable credit equal to 6.85% of new employee wages, or two percent of qualified capital investment, or 50% of the Federal Research and Development Credit. Various employment and investment thresholds along with an aggregate benefit cap limit eligibility.[9] Aggregate benefits were initially limited to $250 million annually.

Though the program had a generous dollar allotment for credits, credits actually issued never came near the $250-million-dollar annual limit. In its best year, it provided $18.4 million in credits. Activity decreased to $745,000 in 2015. The program has had a small job creation impact. Empire State Development reports that companies receiving credits during that time period created 15,582 net new jobs, at a cost to the state of $47,357,602. The program’s impact has decreased in each of the last two years, with only 531 jobs credited as being created by companies receiving the tax credit in 2015.[10]

Because the program does not have a “but for” requirement, ESD’s job figures certainly overstate the program’s true job impact. While the exact percentage of “free rider” jobs is not known, one study estimated that nine of ten jobs created by companies receiving business tax incentives would be created without them.[11] If that is true for the Excelsior Jobs program, the true program impact would be only about 1,500 jobs, three tenths of one percent of New York’s private sector employment growth during the period.

Additionally, a recently issued audit from the State Comptroller’s office points to issues with ESD’s administration of the Excelsior Jobs Program. The describes weaknesses in ESD’s processes in evaluating applications in in confirming job creation claims (note that the agency disputes a number of the audit’s findings.)[12] In particular, the audit noted that “ESD generally authorizes tax credits based on the job numbers and investment costs that businesses self-report without corroborating support….[13]

Why has the program failed to have a significant impact? The evidence points to the fact that because much of its emphasis is on manufacturers and other companies that could locate outside the United States, it does not offer benefits that are sufficiently large to offset the cost disadvantages of creating jobs in New York State, or anywhere else in the United States.[14]

Repeating Failed Policies: Start-Up NY

In announcing the Start-Up NY program, Governor Cuomo said, “Upstate New York has seen too many years of decline, and our communities have lost too many of their young people,… We desperately need to jumpstart the Upstate economy and these new tax-free communities will give New York an edge like we’ve never had before when it comes to attracting businesses, start-ups, and new investment. Today’s agreement on the START-UP NY legislation is a major victory for our Upstate communities as we are now set to launch what will be one of the most ambitious economic development programs our state has seen in decades.”[15]

The promotional materials for the program advertise tax free benefits, and give the impression that the program is relatively easy to access:

“START-UP NY offers new and expanding businesses the opportunity to operate tax-free for 10 years on or near eligible university or college campuses in New York State.

Partnering with these schools gives businesses direct access to advanced research laboratories, development resources and experts in key industries.

To participate in START-UP NY, your company must meet the following requirements:

- Be a new business in New York State, or an existing New York business relocating to or expanding within the state

- Partner with a New York State college or university

- Create new jobs and contribute to the economic development of the local community”[16]

The State Comptroller found[17] that between October 2013 and October 2014, ESD committed $45.1 million to advertise the program, generating more than 15,000 applications during the period. However, despite the heavy advertising for the program, which continued after the period examined in the Comptroller’s report, the program has had almost no job creation impact.

Empire State Development has issued two reports on the program’s progress. In 2014, companies assisted by the program created 76 jobs, while in 2015, assisted companies created 332 jobs. The state tax benefits provided per job through the program were even smaller than those offered by the Excelsior Jobs Program, averaging $1,121 per job created (not including local property tax exemptions).[18] And, because Start-Up NY has no requirement limiting assistance to companies that would not create jobs in New York without the tax credits offered, it is likely that the jobs reported substantially overstates the program’s actual impact on job creation.

The reality is that Start-up NY is extremely complex, the value of benefits to participating companies is small, the program is available in very small areas, and its requirements are difficult to meet. One economic development professional described it as “the worst program I ever saw. I was glad I never had to explain it to a client.”[19]

Effective Approaches to Job Creation and Retention

The tax incentive based approaches used by the State in its Empire Zones, Excelsior Jobs, and Start-Up NY programs have not met the claims made by the governors that championed them. But, other economic development efforts of state and local governments have been shown to be effective. Among them are:

- Regional Economic Development Councils: Regional councils are required to create strategic plans, set clear goals, and disclose progress in meeting established goals as a condition to receive funding for proposed projects. While Regional Council strategies and reports vary in quality, some are well grounded and provide good disclosures of project performance.[20]

- Project Based Assistance: Assistance from the State and localities for plant and equipment capital costs and for customized job training that employs a “but for” test can be effective in inducing companies to create and retain jobs because the amount of assistance offered may be large enough in relation to project size to affect company decisions. ESD, for example, uses “but for” tests in making grants, employs benefit/cost benchmarks, and monitors company performance in meeting performance goals.

- Develop Long Term, Well Integrated Industry Development Strategies: For example, New York, through Empire State Development and other agencies, provided substantial assistance to the development of nanotechnology research and development capacity at the College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, and with local partners, significant financial assistance to the development of the Global Foundries chip-fab facility. In Buffalo, the State has assisted in the region’s effort to enhance its bioinformatics and life sciences concentration at Roswell Park and related institutions. Efforts like these take an integrated approach to industry development.

- Recognize that Retaining Existing Jobs Should be as High a Priority as Job Creation: Because decisions of existing businesses about expansion, contraction or closing can have large effects on a state’s economy, state and local economic development agencies need to focus on understanding the needs of local business and assisting them, where appropriate.

- Support Entrepreneurship: Evidence shows that entrepreneurial training programs increase business startups.[21] New York has an existing program, the Entrepreneurial Assistance Program, that focuses on minorities, women, dislocated workers, public assistance recipients, disabled persons and public housing residents. While the focus on disadvantaged workers is commendable, broader availability could increase the program’s reach.

New York State’s Economic Condition

There has been longstanding concern about the impact of the decline of manufacturing, particularly in upstate New York. The region’s population growth has been very slow, while its central cities have seen significant population declines. Compared to thirty years ago, the residents of upstate central cities are far more likely to live in poverty. These are all significant concerns. But, even upstate, the region’s overall economic health is as good as, or better than the average for nearby states.[22]

Each of the Metropolitan areas in New York State, including those in upstate New York had greater growth in real gross domestic product per resident than the average for metropolitan areas in nearby states. But, the growth of poverty in New York metropolitan areas was below the average for nearby metropolitan areas.

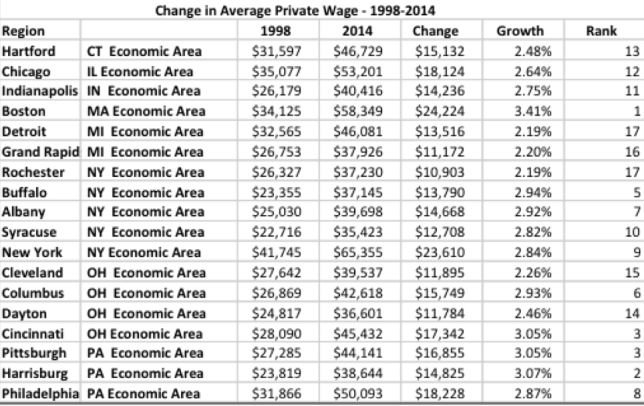

Private sector wage growth in New York State presented a more mixed picture – Buffalo, Albany, and New York City did better than regional average, while Syracuse and Rochester did worse.

Conclusion

While the economic condition of metropolitan areas in New York State, including those in upstate New York, improved relative to nearby areas, in most cases, some places in the state are in very poor economic condition. Upstate cities continue to lose population and have increasingly great concentrations of low income populations. Upstate downtowns have large amounts of vacant commercial space, and upstate cities suffer from blighted, abandoned housing. Minority group residents of upstate cities have average household incomes that are about one third of white suburban residents.

If the lives of residents of central cities are to be improved, New York must address the factors that create concentrations of economically disadvantaged people. These include:

- Schools with high concentrations of economically disadvantaged children. Evidence demonstrates that children from disadvantaged families perform substantially better in schools that have higher percentages of students who are not disadvantaged: https://policybynumbers.com/why-critics-of-upstate-city-school-performance-miss-the-largest-cause

- Single parent families face significant obstacles to success, that also damage the prospects for their children: https://policybynumbers.com/category/single-parent-families.

- Racial segregation is highly related to poverty and poor student performance. https://policybynumbers.com/income-student-achievement.

- Cities have high concentrations of low income residents living in blighted neighborhoods, because most cannot afford to live in better quality housing. More housing vouchers, additional income supplementation, particularly for part-time workers, and increased job accessibility for low skilled workers would help central city residents find better places to live.

- Cities need help in tearing down vacant housing, cleaning up and reclaiming vacant industrial sites and rehabilitating blighted neighborhoods.

But, the focus of highly publicized and expensively marketed economic development initiatives in New York State has been on ineffective programs that have led to negligible job creation. By all accounts they have not succeeded in “supporting significant potential for private sector economic growth” nor do they “give New York an edge, like we’ve never had before.” While many existing economic development efforts at the state and local level produce tangible results, few of them focus on the places in New York State that have done the worst, from an economic perspective. Given the growing bifurcation of the economic conditions of city and suburban residents, more attention should be given to them.

[1] http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-464R,

[2] http://edq.sagepub.com/content/23/1/44.short

[3] Findings of many of these studies are summarized here: http://www.cbcny.org/sites/default/files/report_ez_12012009.pdf

[4] http://taxfoundation.org/sites/default/files/docs/location%20matters_0.pdf

[5] The Tax Foundation calculated state and local tax costs as a percentage of net profits. But since companies seek to minimize overall costs, I compared taxes to total costs. (operating expenses, interest, taxes and preferred stock dividends, but not common stock dividends).

[6] Depending on the capital or labor intensiveness of a manufacturing process, the productivity of labor and labor demand and supply factors.

[7] Peter Navarro, “The Economics of the China Price,” https://chinaperspectives.revues.org/3063, p. 3.

[8] “Governor Paterson Announces Excelsior Jobs Program Launch” http://readme.readmedia.com/Governor-Paterson-Announces-Excelsior-Jobs-Program-Launch/1717095

[9] https://www.tax.ny.gov/pit/credits/excelsior.htm

[10] http://esd.ny.gov/reports.html

[11] http://www.upjohn.org/publications/upjohn-institute-press/state-enterprise-zone-programs-have-they-worked

[12] http://www.osc.state.ny.us/audits/allaudits/093016/15s15.pdf

[13] Ibid., p. 7.

[14] Manufacturing firms continue to operate in New York and the United States because of other kinds of location advantages, such as labor productivity, the need to be close to markets, or insensitivity to production costs.

[15] https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-and-legislative-leaders-announce-agreement-start-ny-legislation-will-implement

[17] “Marketing Service Performance Monitoring” Audit 2014-S-10. http://osc.state.ny.us/audits/allaudits/093015/14s10.pdf

[18] The small benefits provided by the program may reflect the fact that many of the firms participating in the program are start-ups, and have little taxable income.

[19] Communication with this writer.

[20] See for example: http://regionalcouncils.ny.gov/themes/nyopenrc/rc-files/centralny/final%20CNY%20REDC%20plan%20single%20pages.pdf

[21] Benus, J. M., Wood, M. and Glover, N. “A Comparative Analysis of the Washington and Massachusetts UI Self-Employment Demonstrations,” Report prepared for the U. S. Department of Labor by Abt Associates.

[22] Source for this and following tables: U. S. Cluster Mapping Project. http://www.clustermapping.us/region/economic/syracuse_auburn_ny

Excellent essay. Several years ago I was invited (in my role at that time with the incubator association) to a meeting of business and economic-development at which Gov. Cuomo explained his first START-UP NY budget proposal. In fairness to him, he told the group he would rather lower business taxes and operating costs overall, but didn’t have the treasury to lower taxes significantly across the board or the political capital to crack certain cost-drivers like the scaffold law. He came within a hair of admitting that the program was a gimmick designed to put NYS on the map for companies that would otherwise never have considered it. In nearly all her public remarks right up to her departure this month, Leslie Whatley has confirmed that this was in fact one of the more positive outcomes of the advertising campaign. I’d further suggest that he could have come much closer to this goal if he had let Ms. Whatley pursue her own personal advantage in large-company transactions, rather than pushing her to get numbers up on the board fast, which resulted in the program accepting a number of companies not substantially out of the “incubation” stage – a fact that caused its own set of problems. Now that I’ve left the incubator association, I’ll be writing some more about what I think should be the strategic goals of incubator programs as part of regional economic-development strategies. Hint: it has little to do with the job creation numbers the state insists on tracking per dollar invested. BTW, what a piece of nonsense that legislative definition of benefit/cost is, by the way. Each of those factors is important . . . but just to sum them and divide by the credit granted? I can’t think of a single theoretical justification for that ratio. Again, none of this to cavil: you did a great job nailing this down.

Thanks, David. I agree that the benefit/cost calculation doesn’t make much sense, given that the investment counted towards the benefit goes at least in part to the purchases of goods and services from out of state locations. It’s an oversimplified, inaccurate approach.

Excellent article John. I have long believed that providing tax incentives, grants, and other forms of government assistance to businesses of any kind are a poor way to use government to improve the economic status of its citizens. The primary impact is to enrich consultants and business owners, not poor people. Much better to more directly address the root causes of poverty by providing education, food and housing assistance directly to needy families. The jobs will come.

Thanks, John, for the careful analysis. I think that a objective reading of economic success stories must acknowledge the dominance of dumb luck over insightful planning or clever incentives. For every success one might be tempted to attribute to a great & well-executed plan, there are likely a dozen failures with similar plans that achieved nothing. Thus I’m persuaded that public dollars are best spent on activities that improve our ability to take advantage of opportunities that arise without our active participation. This brings us back to investments in human capital and critical infrastructure, not specific giveaways for individual firms or Marshall Plan efforts targeting specific geography.

Thanks, Kent – I mostly agree, and as my post suggests, I think that much of what economic development agencies do focusses on the wrong issues.

John: My 1/25/17 response posted. Please acknowledge. Also is there any charge for the subscription? Hal Peterson

Many thanks. My apologies for not responding sooner.

John